Capital-skill complementarity and regional inequality: A spatial general equilibrium analysis

The economic response of each region to technological shocks depends on the initial endowments and conditions reflected in the current state of the economy.

Abstract

The economic response of each region to technological shocks depends on the initial endowments and conditions reflected in the current state of the economy. In our paper “Capital-skill complementarity and regional inequality: A spatial general equilibrium analysis”, co-authored with Damiaan Persyn (Johann Heinrich von Thunen-Institut and University of Gottingen) and Stelios Sakkas (Economics Research Centre - University of Cyprus), we show that local factors such as trade linkages and skill-group specific vacancy/unemployment rates may be important in explaining spatial patterns in labour markets’ outcomes in response to technological change.

Automation, information and technological progress are the main forces behind the reallocation of income shares among skills, tasks and occupations, as well as a general decline in the share of labour income (see e.g., Karabarbounis and Neiman, 2014; Autor and Salomons, 2018). Since the middle of the 1970s, there has been a steady decline in worker income shares on a global scale. This trend has been well-documented by numerous scholars, including Bentolila and Saint-Paul (2003), Hutchinson and Persyn (2012), and Karabarbounis and Neiman (2014). Within the EU, a similar downward trend can be observed from the 1960s to 2000s, and a stabilization thereafter, as reported in a study by Archanskaia et al. (2019).

While the dynamics of labour income and employment shares have been thoroughly examined at the country level, not much has been said about the regional dimension of technological progress. That is why we investigate the distributional implications of a capital-augmenting technological shift across various regions and skill groups. We also attempt to uncover several local factors influencing how technological change generates an unequal impact across the skills distribution and an uneven effect between regions. We argue that the effects of technology on employment and wage inequality can be substantially more pronounced in certain regions compared to what has been observed at the national level.

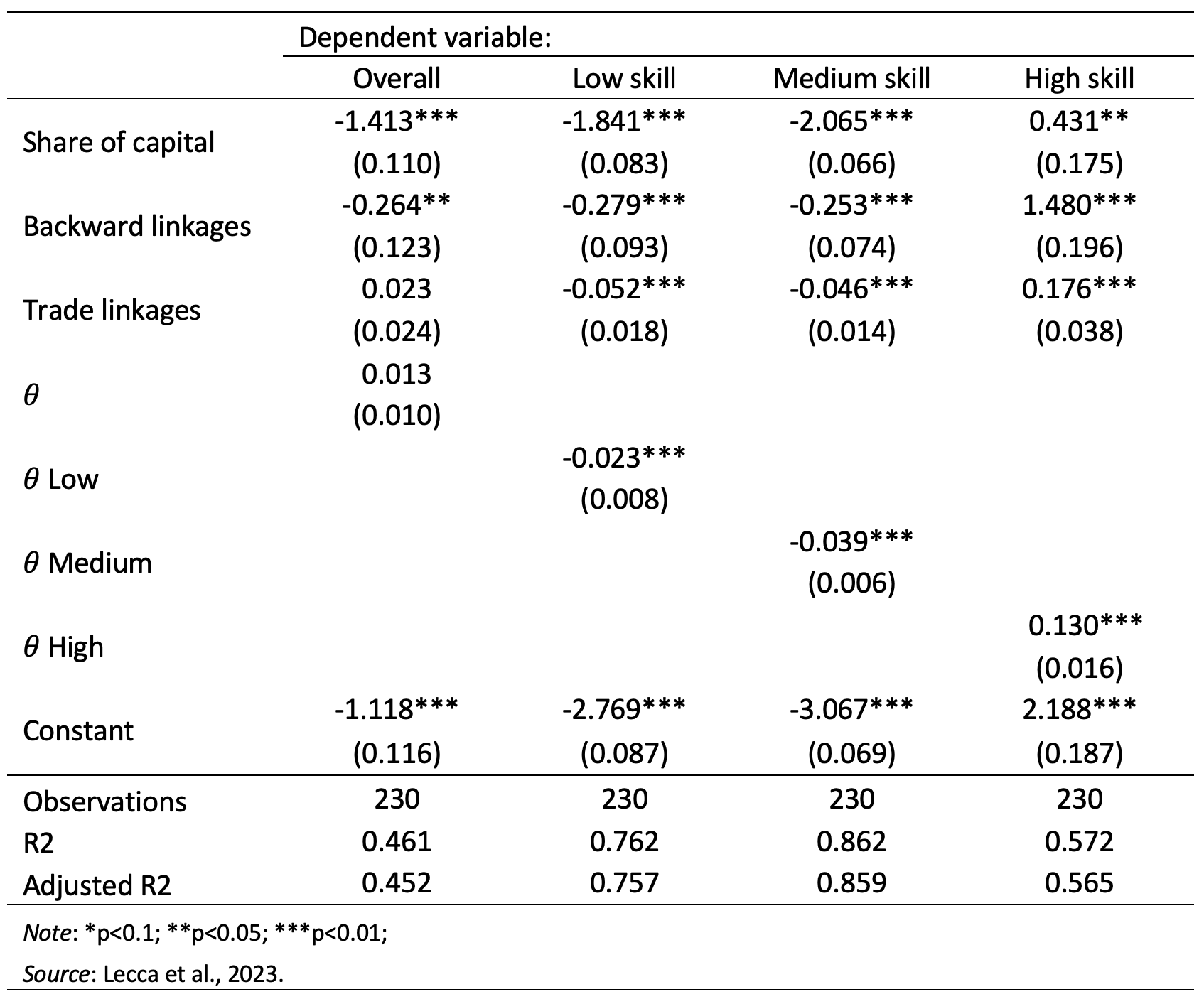

To investigate the effects of technical change, we built a large-scale numerical spatial general equilibrium model that incorporates capital-skill complementarity (following the work of Goldin and Katz, 1998 and Krusell et al., 2000) and search and matching frictions in the labour market following the Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides tradition, as well as a detailed spatial disaggregation that covers 230 EU NUTS 2 regions. Our model allows us to perform counterfactual experiments that involve a symmetric exogenous increase in the productivity of capital. The productivity process is time persistent, and it is implemented as a permanent and deterministic simultaneous perturbation to all sectors and regions. The resulting simulated changes in the labour income shares in each region, derived from counterfactual analysis, are then regressed on a set of initial endowments and initial conditions reflected in the calibrated data of the model. We have identified the initial capital shares, the existing trade linkages, the within region backward linkages, and the labour market \(\theta\) (defined as the vacancy to unemployment ratio), as the main factors influencing the evolution of labour income share after a capital augmenting technical change. Regression results are shown in Table 1.

Overall, we find that capital-intensive regions experience larger shifts of income towards capital at the detriment of labour, indicating that substitution away from labour is stronger in those regions endowed with relatively higher shares of capital. When observing the effects across different skill groups, we find that capital-intensive regions are likely to generate benefit for the labour income of high-skilled workers. However, the same technological shifts are expected to have a negative impact on the income shares of low and medium-skilled workers.

The increase in output resulting from a technological stimulus and re-spent on domestic final goods and services (the backward linkages) is not able to mitigate the decline in the labour income shares generated by productivity shocks. However high skilled workers apparently benefit from an increase in domestic demand. The reason for this is that the increase in demand is mostly addressed to capital intensive sectors.

Moreover, our research reveals that regions with more robust trade linkages, capable of capturing greater trade spillover effects when productivity shocks occur in other regions, experience a significant reallocation of income in favour of high-skilled workers while negatively affecting low and medium skilled workers. In other words, these trade-exposed regions tend to see an increase in income concentration among high-skilled workers, exacerbating income disparities between skill groups within those regions. Finally, labour market pressure would only be beneficial for high skilled workers. Our model suggests that potential higher vacancy rates that might be observed for low and medium skilled workers are not necessarily translated into higher wages.

In addition to the results summarized above, we also find that the efficiency gains generated by technical change ensure that regions with higher shares of high skilled workers will be able to partially or even fully offset the reduction of payments to labour. The model shows a positive correlation (0.86) between the changes in labour income shares and the shares of high-skill workers. This is particularly marked in more advanced regional economies where larger capital-high skill complementarities exist and it is enough to fully counteract the shift away from medium and low skills labour.

In our research, we also focus on the impact of technological shifts on the distribution of employment across skills and on the distribution role of migration. In terms of employment impact, we find some sort of polarization effects in the distribution of employment across skills. The share of medium skilled employment is expected to decrease while the employment shares of high and low skilled employment increase. The reason for this is that typically medium skill wages are higher than low skilled labour therefore creating substitution effects away from medium skills.

Finally, our results show that migration is generally positively correlated with the skill premium. Regions able to attract migrants are therefore those with larger skill premium regardless the skills. It is interesting but not surprising to see that, by and large, migration of all skill types is relatively more encouraged in capital intensive regions. However, the magnitude of this effect is stronger for the case of high skilled workers.

Our analysis therefore shows that the effects of technological development might depend crucially on the innate characteristics and initial conditions of each region. Technological change may create losers, as displaced workers may not always have the adequate skill level needed to find new employment in a rapidly changing labour market. As a result, some regions and countries could take a double hit from shocks like Covid-19 and technical change. While these shocks create incentives to automate and make extensive use of technological advances (such as new forms of work and technologies) at the same time governments ought to find ways to support employment and job retention. Policy makers would be wise to take into account the large differences in regions’ labour markets sensitivity to technological change as revealed by our analysis.

References

- [1] Autor, D., Salomons, A., 2018. Is automation labor share-displacing? Productivity growth, employment, and the labor share. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2018 (1), 1–87.

- [2] Archanskaia, E., Meyermans, E., Vandeplas, A., 2019. The labour income shares in the Euro area. Q. Rep. Euro Area (QREA) 17 (4), 41–57.

- [3] Bentolila, S., Saint-Paul, G., 2003. Explaining movements in the labor share. Contributions in Macroeconomics 3 (1).

- [4] Goldin, C., Katz, L.F., 1998. The origins of technology-skill complementarity. Q. J. Econ. 113 (3), 693–732.